Understanding the Experience of Watching Sci-Fi Films Through Cybernetics

Because I realized how much sci-fi anime has shaped my ideas & images of potential futures...

Spoiler warnings for: Ryuu to Sobakasu no Hime (Belle), Ghost in the Shell, Serial Experiments Lain, and Sing a Bit of Harmony

Hi! When I was in my MA program, I wrote a paper talking about the cybernetic relationship between viewers and sci-fi films. (Anime films mostly!) I revisited the paper recently, and I thought I’d modify it to be a Substack post.

I wrote this paper after having re-watched Ghost in the Shell, because I started thinking about how most of my pre-existing knowledge and images of future, cyberized societies come from sci-fi films and books.

Before I dive into discussing sci-fi anime, I’ll place Annette Michelson’s article "Bodies in Space: Film as 'Carnal Knowledge’” in conversation with Norbert Wiener’s ideas on cybernetics to lay out the ideological framework we’ll be working with.

What’s Cybernetics?

The study of complex systems, specifically the study of how information is processed and transmitted within a system that can include both living organisms and machines/nonliving entities.

An interdisciplinary field that draws from biology, engineering, math, philosophy, and psychology.

Norbert Wiener is regarded as the father of cybernetics, and he defined the field as the study of “control and communication in the animal and the machine.”1

“Animal,” here, refers to any living organism, including humans.

“Information” is another key term in Wiener’s work on cybernetics, which he defines as a “message, whether this should be transmitted by electrical, mechanical, or nervous means.” 2

He further defined a message/information, as “a discrete or continuous sequence of measurable events distributed in time.”3

The message/information is only one component in a cybernetic system — the other is “feedback,” which is the response given to the message.

Key Terms

Message = Information

Feedback = The response a machine or living organism gives to the information it’s fed

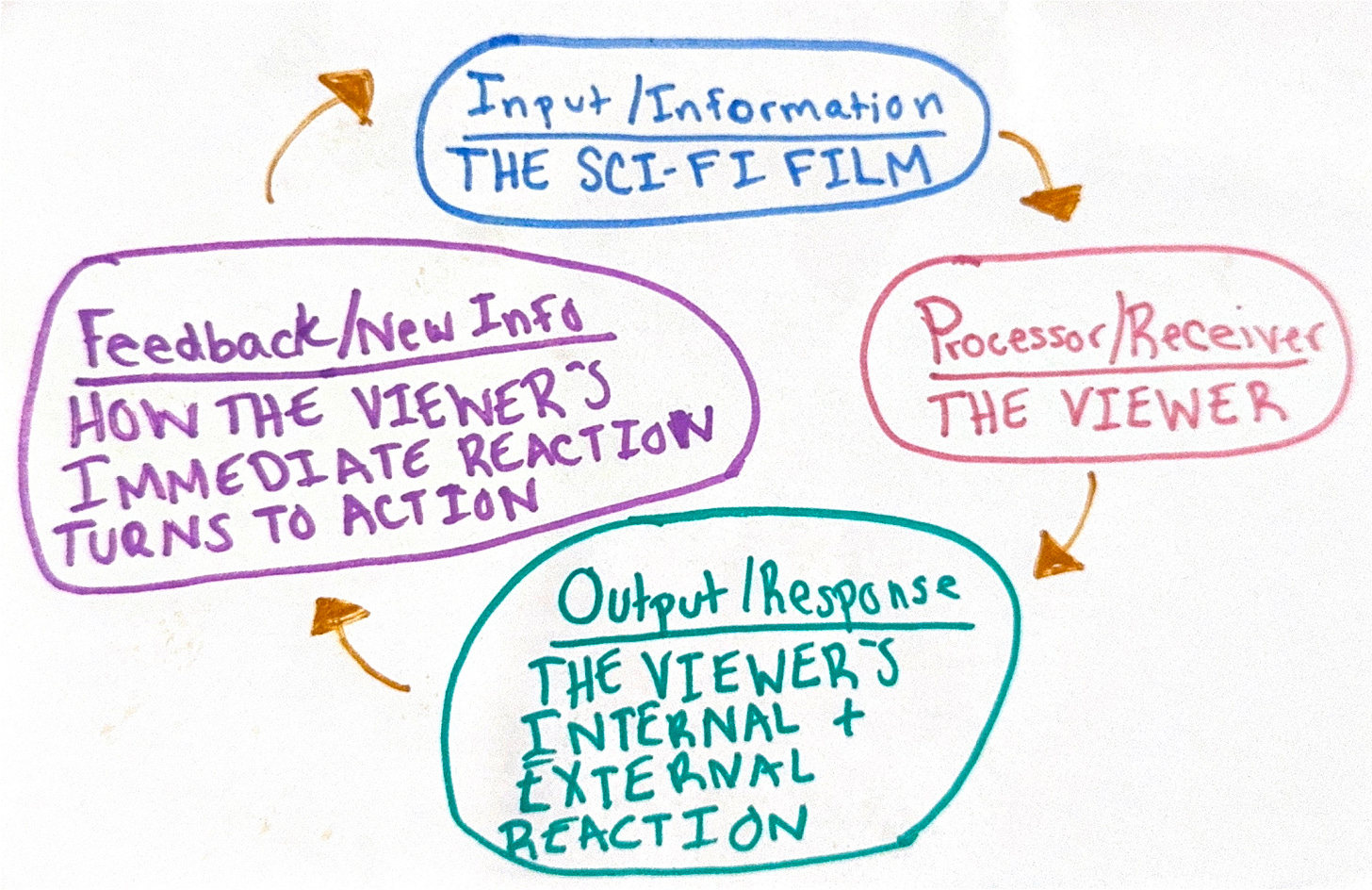

The Cybernetic System of Sci-Fi Spectatorship

If we look at film-viewing as a cybernetic process, we can understand a film to both process and transmit information.

A film processes information, since a story is formed and told through the medium of film — in front of a camera, a sequence of moving images is structured to unfold. Those organized images then unfold again in front of a viewer.

A film transmits information once it’s presented to a viewer, as the sequence of moving images it conveys to the viewer can be understood to be the film’s information/message. The film thus conveys information to a living thing (the viewer).

A viewer can then provide feedback to the film’s information. This feedback can come in various forms: emotional, mental, behavioral, written, verbal, and so on.

Part 1: Cybernetics & Annette Michelson on 2001: A Space Odyssey

In "Bodies in Space: Film as 'Carnal Knowledge,'" art critic Annette Michelson outlines the ways in which Stanley Kubrick’s film, 2001: A Space Odyssey, takes a viewer’s mind and body on a journey through the unfamiliar and unexpected, essentially claiming that viewing the film is a unique sensory and immersive experience. Some film elements she cites as contributing to the creation of this immersive experience include:

The music and sound.

The use of light and shadows to create visual depth.

The sense of expansiveness created by an “overflowing screen.”4

The weightlessness and buoyancy of the camera’s movement, which induces a “restructuring of environment.”5

The narrative’s epic form.

The “triptych” structure of the film.6

Overall, a primary point Michelson makes is that watching the film is a bodily process just as much as it’s a mental one. While Michelson does not use the term “cybernetics” in her essay, her discussion of the full mind-and-body exercise 2001: A Space Odyssey pushes viewers into — and the way in which that exercise forces viewers to experience and process the new and unfamiliar presented by the film in a certain way — resonates with cybernetic theories.

With Michelson’s analysis, we see that in the cybernetic relationship between a film and its viewers, a film can convey a message to both a viewer’s mind and body. This means films can fully sensorily displace you into a new environment and inundate you with information that was previously unknown to you.

I will now point to moments in Michelson’s essay where her language is especially reminiscent of cybernetic language. When discussing the film’s narrative structure, Michelson states:

Kubrick’s film has assumed the disquieting function of Epiphany. It functions as a disturbing structure, emitting, in its intensity of presence and perfection of surface, sets of signals.7

First, let’s consider the idea that the film is "emitting … sets of signals.”8 In cybernetics, signals are transmitters of information; they are used to convey information, as well as responses to information, making them integral to the communication processes in cybernetic relationships.9 In this sense, we can understand 2001: A Space Odyssey’s “intensity of presence and perfection of surface” (a.k.a. its execution and production), as both:10

Being a key component of the information a viewer is fed to process

Being what helps the viewer intake the info experientially. (Again, this idea of experiencing info in a sensorily immersive way, through both the body and mind, is what makes the film a unique production to Michelson.)

Now let’s examine the idea that 2001: A Space Odyssey is able to have the “function of Epiphany,” which is to say the film is able to function as a moment of discovery or revelation of the new and previously unknown. While Wiener does not use the word “epiphany” in his work, concepts of the revealed and the discovered still fit into his construction of cybernetic relationships.

Epiphanies, revelations, and discoveries can occur in a cybernetic system when unexpected information is fed to a machine or organism, resulting in unexpected feedback that then loops back into the system. These moments of unexpected info and feedback, and their constant looping through the system, can lead to new insights and forms of comprehension in the system. These new forms of knowing can be considered epiphanies.

The epiphanies the film induces are a form of feedback in the viewer-film cybernetic system; epiphanies (a.k.a. forms of unexpected knowing and communication), are located both in film and in the viewer’s response to film. We can thus understand the film to be capable of bringing a viewer the experience of an epiphany through the information it is and delivers.

Part 2: Cybernetics & Annette Michelson on 2001: A Space Odyssey

Michelson also references the work of psychologist Jean Piaget, who specialized in studies of child and cognitive development, stating the following:

The structures are to be comprehended in terms of the genetic process linking them. This Piaget calls equilibrium, defined as a process rather than a state, and it is the succession of these stages which defines the evolution of intelligence, each process of equilibrium ending in the creation of a new state of disequilibrium. This is the manner of the development of the child’s intelligence.11

In his cognitive development theories, Piaget analyzed how people adapt to new info and situations their environment presents to them. When the new info presented fits within a person’s pre-existing frameworks for thinking, knowing, and behaving, they can easily adapt to the new info presented to them.

Then there is Piaget’s idea that equilibrium is “a process rather than a state.” It’s this process of seamlessly adapting and harmonizing with your environment in the presence of new information, free of significant disturbances, that Piaget calls the “equilibrium.”12 In cybernetics, “equilibrium” is achieved when the info relayed by one element in the system does not require the receiving element to produce feedback that necessitates significant adaptations that will disrupt the continuous flow of communication across the complex system. In other words, the receiving entity isn’t having any “hey give me a minute to think about that” or “hmmmm” moments in its conversation with the other element.

If the info were to evoke a response from the organism that disrupted the flow of communication — the flow of information and responses — this would equate to what Piaget calls disequilibrium.13 With a disruption of communication comes a disruption of the harmony between the environment/machine and the living organism, as well as between their mutual adaptation processes. Michelson relies on Piaget’s work on child psychology to explain how the film’s narrative both:

Moves in and out of moments of equilibrium and disequilibrium.

Pushes viewers into and out of equilibrium and disequilibrium.

Thus, the film simultaneously serves as art of and an exercise in cognitive development. The film effectively places viewers into the role of a child who develops alongside the narrative.

This understanding of Michelson’s use of Piaget’s work help contextualize her claim that 2001: Space Odyssey exposes a “generation gap,” stating it has “separated the men from the boys’ — with implication by no means flattering for the ‘men.’”14 This is a reference to how compared to younger viewers, older viewers had greater difficulties adapting to and accepting the newness of the information and message 2001: A Space Odyssey delivers — a newness which is conveyed through the film’s narrative structure, plot, scale, images, special effects, and various other artistic components.

In other words, this film has demonstrated an ability to leave older viewers in an unresolved state of disequilibrium; their feedback to the film was negative and their adaptive response was slow. The inability of the older viewer to quickly adapt to the new art form leads to a stagnancy in communication in the cybernetic system between themselves and the film. Consequently, they were left stagnant in their own cognitive development alongside the progressing development of the plot, as well as with a limited understanding of and appreciation for the new artform and information.

On the other hand, younger viewers had positive responses to the film; they were receptive and quick to adapt to the newness of the artform and information conveyed by the film. Effective communication was maintained within younger viewers’ cybernetic relationship with the film. This effective, smooth flow of communication has allowed younger viewers to cognitively develop alongside the film, as well as to deepen their understanding of, appreciation for, and symbiotic relationship with the new artform and its information.

This film is essentially a packet of complex information that can be used to test a person’s ability to adapt to new information and mediums for conveying information.

Expanding Wiener & Michelson’s Ideas to the Entire Sci-Fi Film Genre

Now let’s generalize our conversation on Wiener’s cybernetic theories and Michelson’s ideas about the 2001: A Space Odyssey and apply it to films across the sci-fi genre.

First, let’s work with the idea that all sci-fi films have the ability to immerse our mind and bodies in now-fictitious realities that have the potential to come true. This immersion into a new space and reality ultimately allows the viewer to engage in an information-processing exercise in which they use the info presented in a sci-fi film to understand and provide feedback about potential futures, even if that feedback does not grant the viewer actual control over what comes to be the future.

Furthermore, the displacement from the present — from the here and now of the viewer’s lived reality — into an unfamiliar future means sci-fi films can force the viewer to vacillate between equilibrium and disequilibrium during the viewing process. This, consequently, means that all sci-fi films have the potential to do what 2001: A Space Odyssey does, and test a viewer's ability to adapt to new information and new realities.

The key word here is “potential.”

TL;DR:

We’re now working with the idea that all sci-fi films have the potential to:

Displace a viewer’s mind and body from their here and now and immerse them in a reality humanity has not yet experienced.

Allow a viewer to judge what they want or do not want the future to look like or include, especially in terms of new technologies, spaces, discoveries, and ways of existing.

Sci Fi Anime!

I’ve watched a lot of sci-fi anime. So let’s talks about these ideas specifically as they apply to sci-fi anime!

Mamoru Hosoda’s Belle

Reminder: Spoilers

In 2022, I went to the theater to watch Mamoru Hosoda’s sci-fi, fantasy adventure film, Ryuu to Sobakasu no Hime (2022), known as Belle in English. The film’s protagonist is an introverted high school girl named Suzu, who’s struggling to sing again after her mother’s death. Suzu enters “U,” which is a virtual world with over 5 billion users that people can access via their smartphones.

U is essentially what we’d call the Metaverse. Two things are real game-changers for Suzu in U:

She’s given an extremely beautiful avatar to traverse the virtual world separate from her real body.

She finds herself free from the weight of her real-world identity and trauma.

With her new online identity, Suzu goes on to become a beloved and famous singer in the virtual world.

In U, Suzu also meets a beastly, seemingly villainess avatar, which we eventually learn is controlled by a boy with a younger brother, both of whom are abused by their father. Suzu and the boy’s virtual connection develops into a real-world one, and Suzu is eventually able to reach the two boys in the real world. Overall, Belle depicts how the Metaverse and online interconnectivity between humans can potentially:

Let people explore and develop parts of their identity and relationships they may not have the opportunity to explore and develop in the real world.

Help the powerless gain visibility and connections that can help them with their real-life struggles.

I think one of the most important aspects of Belle are the differences between the way “U” and the real-world are artistically constructed on screen:

Art: U scenes are depicted through immensely detailed and colorful art, with crisp lines and impressive spatial depth, as well as with fluid and smooth animation. These artistic components work together to pull you into the virtual space and construct U as a fantastical, seemingly magical place that’s better than reality. The art used to depict the real-world scenes is also crisp, and the animation is also smooth, but the color palette is more gentle, frequently featuring soft blues and grays.

Music: The musical scoring in U scenes is more upbeat, eclectic, and exhilarating, whereas the musical scoring in real-world scenes is somber, soft, and slow. Furthermore, the real-world scenes often make space for uncomfortable silence, whereas U scenes are seldom without music, dialogue, or indistinguishable chatter coming from large groups of conglomerating avatars.

Space: U scenes are often visually Dionysian, featuring large clusters of avatars intermingling, socializing, and celebrating in shared spaces. On the other hand, in real-world scenes, we often see images of Suzu either alone (usually appearing anxious and depressed), awkwardly navigating school, or quietly interacting with her small friend circle while surrounded by other pocketed groups of friends. The images of social anxiety and social isolation in the real world dissipate with transitions into U, and a viewer is constantly pulled in and out of these two spaces during the film.

The repeated space-jumping between these two worlds results in a viewer fluctuating between adapting to the different info presented by U and by Suzu’s real world. Just like 2001: A Space Odyssey, Belle creates and swings between moments of equilibrium and disequilibrium, while also pushing and pulling a viewer in and out of these two states. Also like 2001: A Space Odyssey, the vacillation between equilibrium and disequilibrium Belle induces is rooted in the film’s artistically-achieved immersive qualities.

U, in a variety of artistic ways, is depicted as being better than the real world. The fact that the villainous avatar who causes mayhem in U is controlled by a young boy with an abusive father ultimately shows us that the horrors of U are only intangible and pixelated reflections of the worse horrors of the real world. However, with this idea, it also seems true that the virtual world will alway have the real world embedded in it.

Slight tangent, feel free to skip:

This idea of the negative aspects of the internet only being emulations of the negative aspects of the real world can be understood to have two different implications:

On one hand, the virtual world issues may be perceived as having lower stakes than those of the real world. The issues that plague the online world are thus constructed as less pressing and inconsequential when placed in the context of real-world issues, which are inherently more pressing and consequential, since they involve people’s livelihoods and can be escalated to life-or-death stakes. Therefore, the fundamental issues for and between humans will always be rooted in the real world — the online world will always just be a diluted echo of those issues. In this way, Belle can be seen as framing existence in U as a form of living that’s more harmless and less weighted than in the real world. Pairing this idea with the notion that it’s only through U that Suzu begins her healing process and is able to save the two boys, U can be seen as a place that truly augments the lived experience, rather than takes over it.

On the other hand, we can see also see this as representing the inescapability of the ways in which the real-world becomes embedded in the online world, thus challenging ideas of the potential for a tech-utopia (or at least a tech-driven utopia). This idea appears in plenty of recent scholarship that views technology not as an inherent equalizer, but as a tool for reproducing bias and inequality.15 With this idea in mind, U can be seen as an extension of reality, rather than an augmentation of it.

As I left the theater with my friend after watching Belle, I struggled to reconcile my desire for the Metaverse to be real (because it looked like so much fun), with my understanding of how it would become another major artifact of distraction, diverting people from tackling real-world issues. I worry the Metaverse would tempt people to escape our planet and our lived reality — that it would become an excuse to abandon attempts to save and heal the world we already live in. My friend echoed these sentiments when in our chat about the Metaverse she said, “I think the boys over in Silicon Valley need to take a break from playing with their tech toys and learn how to live in reality.” How can we have something like the Metaverse without the risk of mass disconnection from the real world? Is that possible?

… sigh…

Mamoru Oshii’s Ghost in the Shell

Reminder: Spoilers

While Belle left me feeling partially thrilled about the potential ways the Metaverse and other tech innovations could augment our real-world experiences, I also understood my friend’s wholly technophobic sentiments. I felt a similar uneasiness after watching Mamoru Oshii’s film, Ghost in the Shell (1995).

Ghost in the Shell takes place in a technologically advanced society in 2029, in which people can augment their bodies with robotic components to become cyborgs. Many people in the film have cyberbrains that allow everyone’s brains to be linked together, creating a cybernetic network in which everyone’s minds can exist as one. The film follows the advanced cyborg and police force member, Major Motoko Kusanagi, as she attempts to track down the "Puppet Master," a sentient AI which/who is (depending on how you perceive sentient AI) hacking people’s cyberbrains and altering their memories.

Ghost in the Shell portrays the potential consequences of humans becoming too integrated with technology that is external to their natural being. One consequence presented is a sentient AI becoming hostile towards humans and using its full integration with the cyber networks humans have become hyper-dependent on to overpower and control humanity. Another consequence presented is more internal…

Kusanagi claims, as a cyborg, she has “a tendency to be paranoid about our origins."16 We see Kusanagi struggle to confirm her own humanhood, debating if her “ghost” — or her individual consciousness and memories stored in her human-like, cyberized form — is enough for her to still be considered human, or if she’s something else. These quiet horrors, largely rooted in displacement from one’s own human identity, are conveyed not just through the dialogue and plot, but also by:

The stark, industrial environment art.

The expressionless faces of the cyborgs.

The ominous and ambient soundtrack.

When watching this film, I was made uneasy by the idea that we can incorporate enough technology into the cybernetic systems within our bodies, as well as between our bodies and our environment, that our memories and sense of self become so altered and mangled, leading us to forget our own origins and lose our ability to confirm our own humanity the way we should be able to confirm our own humanity — that is to say, merely by existing.

The way my friend and I processed Belle’s images, storyline, and information differently, and the way in which Belle and Ghost in the Shell made me feel differently about the potential for a more cyberized society, illustrate the power of sci-fi films. These are just two examples of how sci-fi films can shape a viewer’s attitude towards the technology of the future and the potential sociocultural changes tech advancements may bring. This is to say all sci-fi films allow you to explore spaces that are not yet a reality, and move and think alongside fictional characters who are experiencing that not-yet-our-reality reality.

Why Does This Matter?

If we understand all sci-films as being capable of creating a information-processing system between their content and a viewer, as well as of immersing viewers in future scenarios through their artistic conveyance of information (even if all are not crafted to fully reach this potential), we can thus understand all sci-films as being capable of shaping how we perceive futuristic technological and scientific endeavors. In this sense, there is a great power cybernetics bestows upon all sci-fi films. With this being the case, it becomes important to analyze collections of sci-fi films from a given era to attempt to identify potential trends in those films’ messages. If it seems like most of the films of a given era are sending a similar message, it may be important to ask if our perception of technology and the future is being intentionally molded.

Ryūtarō Nakamura’s Serial Experiments Lain

Reminder: Spoilers

Another dystopian sci-fi show released in the late 90’s was Ryūtarō Nakamura’s Serial Experiments Lain (1998). The show follows Lain, a middle school girl, as she enters "The Wired," which is also like our modern-day concept of the Metaverse, as it allows people to traverse the internet as a physical space separate from their bodies. For Lain and the other characters, the lines between the real and virtual world start to blur, and people start electively abandoning their bodies to live fully interconnected with others in the online network. Underlining the show’s narrative are the struggles people face to connect with and communicate with others in the real world. The show also explores the ways in which the internet can:

Offer an escape from this issue with interpersonal relationships instead of remedying it.

Heavily influence a person’s identity in both beneficial and detrimental ways.

The art, animation style, and plot of Serial Experiments Lain work together to convey a dystopian atmosphere, as well as to place humans face-to-face with the ways in which developing an interdependence with technology can distort our sense of reality and sense of self. The show relies on a dark and murky color palette to convey a sense of lifelessness, as well as a surreal art style — especially when depicting the human body — to help convey (or, rather, warn) of the ways in which technology can create a dissonance between humans and their humanity.

Consistencies in Vibes Across Late 80s & 90s Sci-Fi Films

There are numerous other sci-fi anime released in the same era as Ghost in the Shell and Serial Experiments Lain that depict the tragedies, issues, and rifts between humans and their humanity that can come with tech advancements and human interdependence with technology. Some notable works (not all anime) include: Akira (1988), Total Recall (1990), Blade Runner (1982), Memories (1995), and Neon Genesis Evangelion: The End of Evangelion (1997).

Considering the historical context of the 1990s, the surge in films exploring the nature of hyper-cyberized societies is not coincidental. The releases of many of the aforementioned dystopian sci-fi films correlate with the proliferation of the World Wide Web, which was developed in 1989 and made available for public use in 1993.17 These films can be viewed as exploring how the invention of the Web would impact humanity, society, and the natural world. We’re now amid another age of rapid technological innovation (or perhaps it’s just been one continuous age of innovation), with great strides (and investments) being made in the realm of artificial intelligence, robotics, bioengineering, and virtual and augmented realities. As a result, we’re seeing films being released in the past decade that explore the potential of the next internet wave, such as Belle. However, many of these newer films tend to maintain a more positive outlook on tech innovation (or at least weave more threads of positivity throughout their narrative) than their 1990s predecessors.

Yasuhiro Yoshiura’s Sing a Bit of Harmony

Reminder: Spoilers

Another modern, AI-optimistic anime film is Yasuhiro Yoshiura’s Sing a Bit of Harmony (2021), which tells the story of an AI named Shion, who looks like a young girl and is sent to high school with the film’s protagonist, Satomi. Shion’s main priority is making Satomi happy and protecting her. While Shion proves to be harmless and friendly towards humans, the corporation that developed her still tries to “delete” her. As they try to evade the corporation, Satomi and Shion develop a profound bond and come to deeply care for each other.

In this film, we see the potential for a peaceful, meaningful coexistence between people and AI, with the main enemy being humans — specifically controlling humans. (Even more specifically, humans who desire total control over the technology they create, even after it gains sentience.) The film’s optimism is conveyed through its upbeat soundtrack, which frequently features songs that are a mix of J-pop and jazz, as well as through its bright color palette, fluid animation, and choreographed musical numbers.

A Change in Vibes Across Contemporary Sci-Fi Films

Other recent sci-fi films (not all anime) that depict more harmonious relationships between humans and various forms of advanced technologies, such as AI, robotics, and spacecrafts include: Her (2013), Tomorrowland (2015), Planetarian: The Reverie of a Little Planet (2016), Eden (2021 anime), and Space Sweepers (2021).

The Importance of the Shift in Sci-Fi Film Narratives

I mention these different sets of sci-fi films to demonstrate a shift in the types of narratives relayed by sci-fi films released circa-1990 and those released in the last 15 years or so.

Before we move ahead through the conclusion, I want to clarify that I’m not saying all recent sci-fi films positively and optimistically depict technological advancements. Rather, I’m saying that we’re seeing more films exploring the possibilities of a positive future through technological integration and advancement than we did in the ’90s. (A much less extreme claim lol.) Now that that’s cleared up… onward!

To recap, sci-fi films have the power to:

Convey information about unknown potential futures.

Immerse a viewer’s mind and body in futures that have yet to be lived and that have only been imaginatively conceived by humans.

In doing so, sci-films have the power to shape our attitudes towards technological futures. I’ve spent the earlier half of my life nearly exclusively consuming dystopian sci-fi content, but as I’ve continued to watch the more contemporary releases of the past decade, I’ve been consuming more positive portrayals of tech innovation and cyberized societies.

While the images I’ve previously consumed of dystopian cyber-futures still linger prominently in the back of my mind, I notice how the newer sci-fi films have heavily altered how I imagine the potential for new technologies. Whereas older sci-fi films left me feeling totally apprehensive of humans over-relying on and over-investing in technology, newer sci-fi films leave me feeling hopeful about the potential ways we might beneficially integrate technology into our lives. (Assuming, of course, the technology is integrated correctly and ethically, and that the right people are developing the technology… you know… people with ethics and principles and a love of humans).

This is to say that even if that positive future is not definite, newer sci-fi films make me feel like it’s possible for humans and the tech we develop to live in a symbiotic relationship, rather than in a constant power struggle — but it’s up to us to create that future.

I believe sci-fi’s power to profoundly shape our conceptualization of the future is rooted in the genre’s “fiction” label. It’s easy to consume media and narratives labeled as fiction without thoroughly questioning the concepts they lead us to internalize, because we think we’re aware it’s fake. Consequently, we fail to recognize the ways in which fictitious media molds our perception of reality. By presenting us with a future we’ve never experienced, but one which we may hope to become real, sci-fi films can imbue us with a nostalgia for the future — a yearning for the to-be-experienced — through their ability to immerse our bodies and minds in a reality different from humanity’s past or present.

Thus, the power of the sci-fi genre cannot be underestimated. For instance, most leading Metaverse experts and researchers, such as Matthew Ball, often cite Neal Stephenson’s 1992 sci-fi novel, Snow Crash, in their discourse on conceptions and predictions of what the Metaverse can potentially be.18 Many of the AI and robot assistants we see in early sci-fi films have come to manifest in their own ways — think of Apple’s Siri, Amazon Alexa, Google Assistant, ChatGPT, and Claude. Even Star Wars is starting to look more like a potential reality as privatized space exploration advances. The immersive experience and the information exchange that occurs when watching a sci-fi film can imbue people with ideas and desires for a future that they come to make a reality; they can also give people a false sense of control over the tech-based narratives they hope to manifest in reality.

Considering the potential power sci-fi films are given when we understand them as a cybernetic experience, as well as the shift in sci-fi film narratives over time, there are questions we must ask ourselves while watching sci-fi films if we’re to be thoughtful consumers who are aware of the information-processing system we engage in when we watch such films. For instance, what type of new info are we being fed by the art we consume, and from where is this info originating? How will that new info alter the cybernetic system of which we are a part? Do we or the films we watch have more power in our cybernetic relationship, or is the power balanced? Who benefits from the certain perceptions of tech being perpetuated by the sci-fi films produced, released, and marketed in a given era?

In the age of data, information, and technology (and loads of it), understanding the origins and consequences of all the information we consume, even information from works of fiction, is important if we’re to have any control in shaping humanity’s future.

Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine (Cambridge, MA: The Technology Press, 1949), 1.

Ibid, 16.

Ibid, 16.

Annette Michelson, “Bodies in Space: Film as ‘Carnal Knowledge,’” Artforum, February 1969, https://www.artforum.com/print/196902/annette-michelson-on-stanley-kubrick-s-2001-a-space-odyssey-36517.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Norbert Wiener, Cybernetics: Or Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine, 54.

Annette Michelson, “Bodies in Space: Film as ‘Carnal Knowledge.’”

Ibid.

Saul Mcleod, “Piaget’s 4 Stages Of Cognitive Development & Theory,” Simply Psychology (Simply Scholar, Ltd, May 3, 2021).

Ibid.

Annette Michelson, “Bodies in Space: Film as ‘Carnal Knowledge.’”

Examples/recommended readings: Safiya Umoja Noble’s Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism, Cathy O’Neil’s Weapons of Math Destruction, and Thomas S. Mullaney et al.’s Your Computer Is on Fire.

Ghost in the Shell, directed by Mamoru Oshii, released March 29, 1996, produced by Production I.G, 42:25.

A short history of the web.” CERN. CERN. Accessed April 10, 2023. https://home.cern/science/computing/birth-web/short-history-web.

Matthew Ball, The Metaverse: And How It Will Revolutionize Everything (New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 2022), 9.

The screenshots included in this article are used under the Fair Use doctrine for the purposes of commentary, criticism, and educational analysis. All visual content is the property of its respective copyright holders. No copyright infringement is intended.

Full citations for screenshots:

IMAGE 1: Belle, directed by Mamoru Hosoda, released July 16, 2021, produced by Studio Chizu, 20:54, viewed on Prime Video.

IMAGE 2: Ghost in the Shell, directed by Mamoru Oshii, released March 29, 1996, produced by Production I.G, 33:29, viewed on Tubi.

IMAGE 3: Sing a Bit of Harmony, directed by Yasuhiro Yoshiura, released January 23, 2022, produced by J.C.Staff, 1:18:24, viewed on Crunchyroll.

Hi! Loved the post and love your content. I think what you're talking about Sci fi is so prevalent at the moment - especially with the advent of AI. Anime allows us to suspend our imagination and often is quite prophetic. As a shameless plug, if you're interested, I also write about video games/personal journey on my profile as well.